Dolor torácico infantil

24 - 09 - 2014

15-minute consultation: A structured approach to the assessment of chest pain in a child

Samuel A Collins ; Michael J Griksaitis; Julian P Legg

Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed Agosto 2014;99:122-126 (Free)

Introduction

Chest pain is a relatively common presenting symptom in children that causes a great deal of anxiety in patients, parents and healthcare professionals. It affects approximately equal numbers of children under and over 12, with no particular gender bias. The anxiety surrounding chest pain most likely arises from the association between chest pain and cardiac ischaemia in adults and media coverage of sudden cardiac deaths; however, underlying cardiac pathology is rare in children with chest pain and parents/patients can usually be reassured that there is not a serious underlying cause. The two largest studies to date looked at a total of 8136 children presenting to emergency departments with chest pain and found that only 0.6–1% of these had a cardiac cause for their pain. Despite this, a study of 100 adolescents with chest pain showed a significant impact on quality of life with over 40% absent from school with their chest pain and 44% believing their chest pain was a result of a ‘heart attack’. This study highlights the degree of unwarranted anxiety that chest pain can cause. A chest pain consultation should, therefore, focus on acknowledging the patient/parental fears, exclusion of rare, serious underlying pathology and appropriate reassurance.

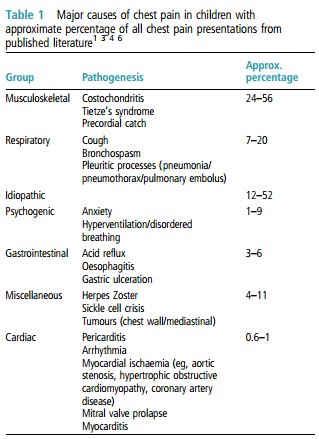

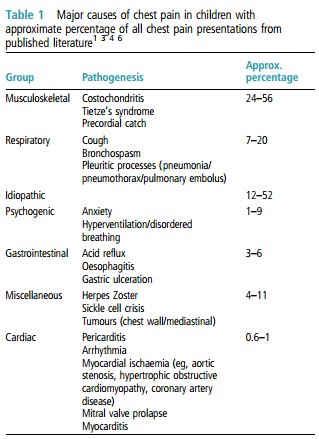

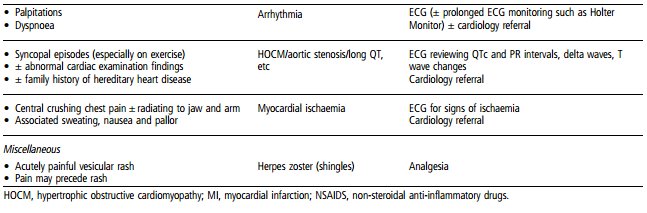

Table 1 summarises the major causes of chest pain in approximate order of frequency. Although the majority of patients do not have a serious underlying diagnosis, it is clearly important to quickly assess those that may be at increased risk.

Previous studies have shown that a thorough history and physical examination are sufficient, in the vast majority of cases, to exclude a serious cause for the pain.

Targeted diagnostic testing can then be performed to address concerns identified. The potential causes of chest pain have been reviewed more fully by Ives et al but here we present an approach to assessment.

History

A detailed history is vital when assessing a child with chest pain as a thorough enquiry into the nature of the pain and associated features may be all that is needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

Age is a consideration when assessing these patients; adolescents are more likely to have musculoskeletal or psychogenic causes for chest pain, while young children may interpret a wide range of symptoms or chest sensations as pain.

Box 1 describes some of the ‘red flag’ features that should alert to a potential cardiac cause.

The differing characteristics of the chest pain in each of the main categories are as follows:

Musculoskeletal

Usually well localised and can often be reproduced with palpation or gentle sternal pressure.

Worse with movement, coughing and inspiration.

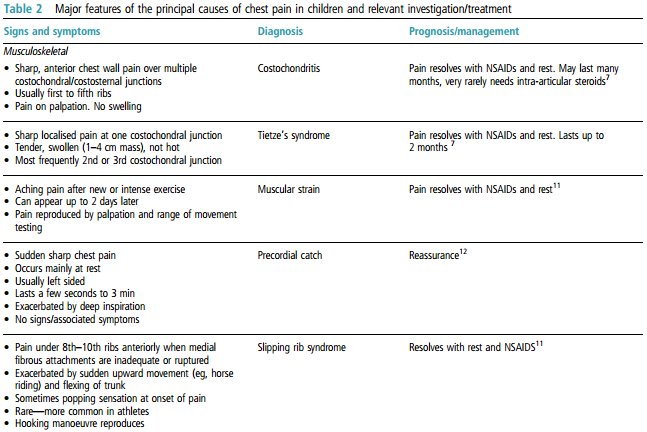

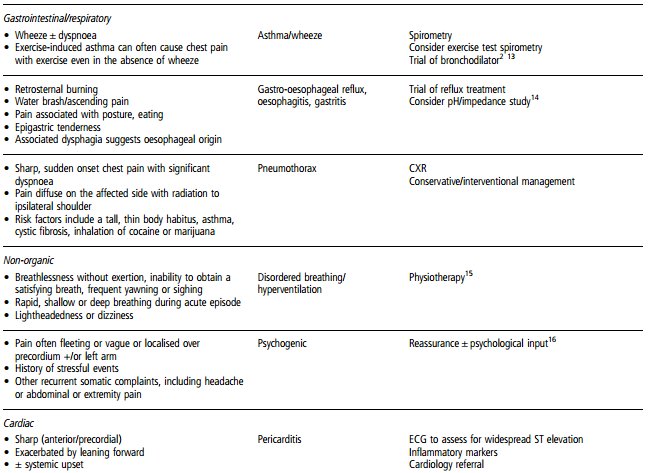

See table 2 for more details.

Respiratory

Pain from asthma often described as ‘tightness’, associated with wheeze, shortness of breath and dry cough.

Pleuritic pain is usually sharp and localised, exacerbated by inspiration and coughing.

Pain from pneumothorax will be ipsilateral and is often felt in the upper anterior part of the chest.

Psychogenic

Often recurrent with particular stressors.

History of anxiety (particularly panic disorder) and/or stressful life events.

May be associated with hyperventilation.

Gastrointestinal

Often retrosternal or epigastric, but may also be central.

Typically burning or sharp in nature.

May be exacerbated with eating or posture.

Can be associated with heartburn, water brash (production of excess saliva in response to acid in the oesophagus) or dysphagia.

Cardiac

Centrally located and may radiate to the left arm/jaw region.

Typically described as crushing pain or heaviness, like ‘an elephant sat on my chest’.

Associated autonomic symptoms such as sweatiness, nausea or pallor.

Chest pain on exertion is particularly significant, especially if the pain is of a typical cardiac nature.

Associated presyncope, syncope and palpitations.

It is also important to include the following key areas of enquiry :

Is there any history of trauma or preceding new or intense physical activity?

How long has the pain been present?

Is the pain associated with any particular activities such as eating or exercise?

How often does the pain occur and how long does each episode last?

Are there any exacerbating factors, for example, exercise, certain positions, movement and coughing?

Are there any alleviating factors such as positional changes, rest, analgesics and antacids?

Any dyspnoea, cough, wheeze or other respiratory symptoms?

Have there been any associated constitutional symptoms such as fever, anorexia and weight loss?

Are there any potentially cardiac-related symptoms or risk factors, including palpitations, syncope, family history of sudden death, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD), arrhythmias, previous Kawasaki disease or congenital heart disease?

Any vomiting, heartburn, dysphagia, water brash or other gastrointestinal symptoms?

Are there any underlying medical conditions that may be associated with chest pain such as asthma, Kawasaki disease and sickle cell disease?

Is there any history of possible substance abuse?

Any recent stressors at home or school? Any problems with anxiety?

Table 2 summarises the clinical features of the principal causes of chest pain in children and provides concise details of further management and prognosis.

Physical examination

A thorough physical examination will often elicit signs that can help make a definitive diagnosis.8 It is important to include the following:

A full set of vital signs, including blood pressure and oxygen saturations.

Assessment of general appearance, including colour, level of alertness, breathlessness and evidence of anxiety/distress.

Evaluation of pulse volume, rate and character.

Range of motion studies of the arms to elucidate any relationship to pain.

Inspection of chest for signs of trauma, bruising, asymmetry and localised swelling.

Palpation of chest for tenderness (particularly at the location of described pain), crepitus, heaves or thrills. Hooking manoeuvre; hook fingers under lower costal margin and pull anteriorly—reproduces pain in slipping rib syndrome.

Auscultation of lung fields for air entry, wheeze, crackles and pleural rub.

Auscultation of precordium for heart sounds, murmurs and pericardial rub.

Examination of abdomen for signs of tenderness (particularly epigastric), trauma and organomegaly.

Further investigation and intervention

Acknowledging parental/patient anxiety and providing appropriate reassurance is usually all that is needed. Further investigations and interventions are reserved for those cases where the history and examination do not suggest a diagnosis or concerning features have been identified.

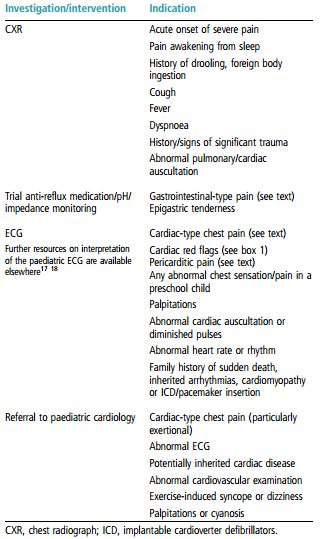

Table 3 summarises the principal indications for further investigation/intervention.

Table 3 Chest pain—indications for further action

Follow-up

Follow-up arrangements are determined primarily by the final diagnosis. Following initial review, many patients with a benign condition can be discharged and reassured regarding the likely diagnosis and its natural history. However, in some patients, chest pain can become recurrent and severe, interfering significantly with activities of daily life. A follow-up study of 149 children presenting with chest pain showed that 43% still experienced chest pain at 6 months. Although the diagnosis was often altered over this time period, the commonest change was to a diagnosis of idiopathic chest pain and no serious organic disease was picked up after the initial assessment. Likewise, the Harvard study of 3700 patients over 10 years recorded no cardiac deaths in patients discharged from their clinic. These two studies provide further evidence that appropriate initial assessment of chest pain is all that is needed to reassure and discharge the majority of patients.

In certain circumstances, particularly in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, it is pertinent to arrange provisional follow-up that can be cancelled should symptoms resolve. In the majority of these cases, follow-up will be important primarily to manage the patient/parents’ ongoing anxiety surrounding the chest pain rather than monitoring for new signs of serious pathology.

References

Selbst SSM, Ruddy RMR, Clark BJ, et al. Pediatric chest pain: a prospective study. Pediatrics 1988;82:319–23.

Danduran MJ, Earing MG, Sheridan DC, et al. Chest pain: characteristics of children/adolescents. Pediatr Cardiol 2008;29:775–81.

Drossner DM, Hirsh D a, Sturm JJ, et al. Cardiac disease in pediatric patients presenting to a pediatric ED with chest pain. Am J Emerg Med 2011;29:632–8.

Saleeb SF, Li WY V, Warren SZ, et al. Effectiveness of screening for life-threatening chest pain in children. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1062–8.

Pantell RH, Goodman BW, Goodman W. Adolescent chest pain: a prospective study. Pediatrics 1983;71:881–7.

Rowe BH, Dulberg CS, Peterson RG, et al. Characteristics of children presenting with chest pain to a pediatric emergency department. CMAJ 1990;143:388–94.

Proulx AM, Zryd TW . Costochondritis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician 2009;80:617–20.

Selbst SM, Ruddy R, Clark BJ. Chest pain in children: follow-up of patients previously reported. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1990;29:374–7.

Ives a, Daubeney PEF, Balfour-Lynn IM. Recurrent chest pain in the well child. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:649–54.

Kane DA, Fulton DR, Saleeb S, et al. Needles in hay: chest pain as the presenting symptom in children with serious underlying cardiac pathology. Congenit Heart Dis 2010;5:366–73.

Gregory PL, Biswas AC, Batt ME . Musculoskeletal problems of the chest wall in athletes. Sports Med 2002;32:235–50.

Gumbiner CH. Precordial catch syndrome. South Med J 2003;96:38–41.

Wiens L, Sabath R, Ewing L, et al . Chest pain in otherwise healthy children and adolescents is frequently caused by exercise-induced asthma. Pediatrics 1992;90:350–3.

Czinn SJ, Blanchard S. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in neonates and infants : when and how to treat. Paediatr Drugs 2013;15:19–27.

Burton CD . Hyperventilation in patients with recurrent functional symptoms. Br J Gen Pract 1993;43:422–5.

Lipsitz JD, Gur M, Albano AM, et al . A psychological intervention for pediatric chest pain: development and open trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2011;32:153–7.

O'Connor M, McDaniel N, Brady WJ. The pediatric electrocardiogram: part I: age-related interpretation. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26:506–12.

O'Connor M, McDaniel N, Brady WJ . The pediatric electrocardiogram part II: Dysrhythmias. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26:348–58.